Music Modes Chart and Circle of Fifths by Endorpheus

Music Modes Chart and Circle of Fifths by Endorpheus

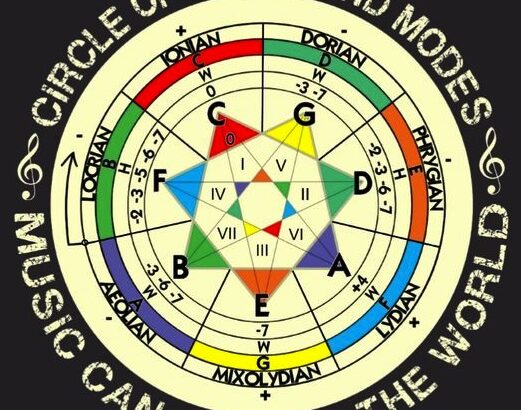

Musical modes are variations of musical scales by moving the tonic (the root note) up or down a number of degrees and beginning the scale from that new starting point, while retaining the same notes of the scale. As with everything human made or discovered, the modern modes have a long history behind them. The concept began in ancient Greece and underwent stages in which they grew from 4 modes to 12 over the centuries. Early Christian, Jewish and Eastern cultures contributed to what became known as the “church modes of the Middle Ages” in Europe. Today, the modes retain their original Greek names: the Ionian, Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian, Locrian.

These seven modes can be transposed onto our current twelve note system to create all twelve keys. Various modes are used throughout all musical styles, heavily for example in jazz, but by musicians of all other genres as well. Each mode within each key creates a different emotional feel elicited from the listener due to the various intervals played. There is agreement that certain abstract concepts and emotions such as “triumphant,” “somber,” and “exotic” can be attributed specifically to certain modes. Each one has its own character. When combining each mode to each key we have a plethora of possible variations with which to approach music composition and improvisation.

1. Music makes the mood/mode

The idea that modes produce emotions is ancient and goes even further: that exposure to certain modes influences behavior. The great Plato himself believed that soldiers should only listen to Dorian Phrygian modes which elicit strong powerful vibes, but not Lydian or Ionian as they to feel more dreamlike, innocent – not qualities wanted in warfare. Like the ancient Chinese concept of a people’s music representing the behavior of the people themselves, Plato felt that music can also go the other way and influence the behavior of people. Aristotle, in Politics, writes that the essential differences between the modes create a different effect on all those who listen, “Some of them make men sad and grave .. enfeeble the mind … produce a moderate or settled temper” or “enthusiasm” as in the Phrygian mode.

The idea that modes produce emotions is ancient and goes even further: that exposure to certain modes influences behavior. The great Plato himself believed that soldiers should only listen to Dorian Phrygian modes which elicit strong powerful vibes, but not Lydian or Ionian as they to feel more dreamlike, innocent – not qualities wanted in warfare. Like the ancient Chinese concept of a people’s music representing the behavior of the people themselves, Plato felt that music can also go the other way and influence the behavior of people. Aristotle, in Politics, writes that the essential differences between the modes create a different effect on all those who listen, “Some of them make men sad and grave .. enfeeble the mind … produce a moderate or settled temper” or “enthusiasm” as in the Phrygian mode.

2. Major and minor modes and the intervals between

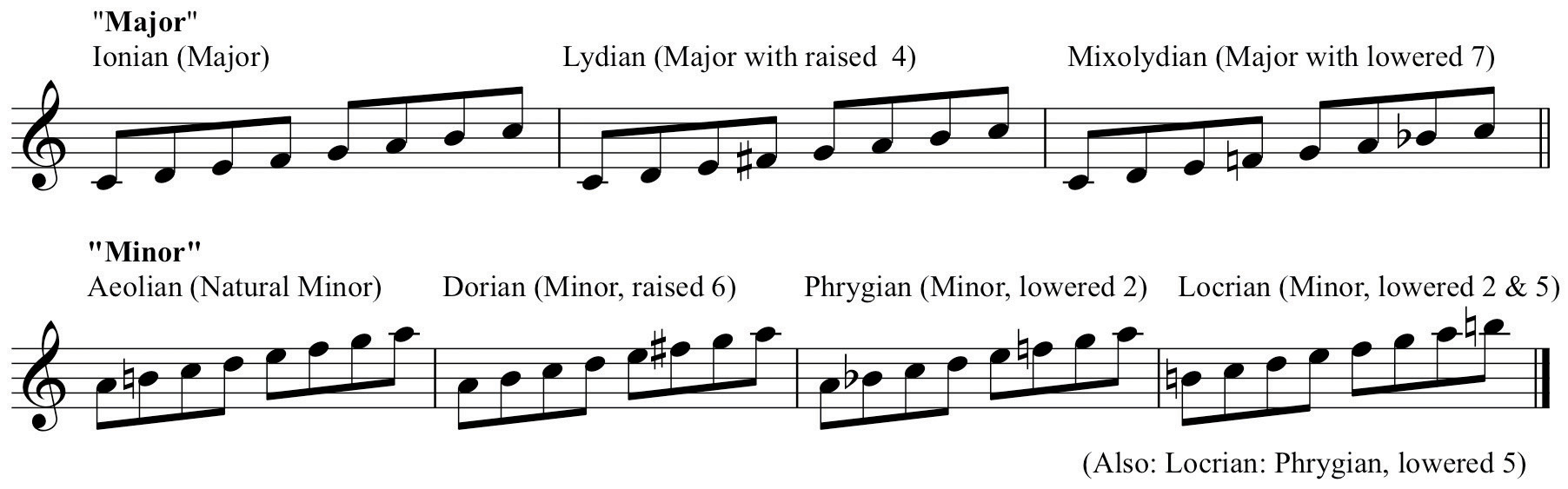

The most striking difference between the 7 modes are the 3rd interval, which determines whether a mode in question has a minor or major feel to it. This is the interval between the root note of the scale and the third note. If it is a major third (whole step between the 2nd and 3rd note) and then the mode is major. If it is a minor third (half step between the 2nd and 3rd notes) then the mode is minor.

The there major modes are Ionian, Lydian and Mixolydian. Because, for example, in C Major the 3rd between C and E in Ionian is major, the third between F and A is major in Lydian, and in Mixolydian as well the third between G and B is major. On the other hand, the four minor modes are Dorian, Phrygian, Aeolian, and Locrian. The post will cover the history, characteristics and emotions associated with the major modes only. Importantly, most might agree that it is the key, not necessarily the mode, that determines the emotional feel of a piece of music. That said, musicians employ a wide variety of modes across all keys to capture their emotional intent and messages

3. Mode I: Ionian

The first mode is the Ionian. It is basically the modern major scale that most of us know: doh re mi fa so la ti.” The sequence of steps is W, W, H, W, W, W, H (with W being whole-step and H being half-step). The Ionian mode was singled out to be named in 1547 by Henricus Glareanus, a Swiss humanist in his work, “Dodecachordon,” a treatise on music that expanded the contemporary eight mode church musical system. Major and minor modes of the time were increasing in significance and Glareanus saw a need to incorporate them into the current agreed upon church modes, therefore naming the major mode Ionian and also adding Aeolian which, by the way, is the current modern minor mode to be discussed in another post.

Ionian in the key of C nearly universally the first scale that children and future musicians are taught. It is generally thought of as happy, bright, innocent, reassuring, cheery, joyous and absolutely “major.” When played at a slower tempo it can sound royal and majestic – add a little tempo and we have triumphant.

Examples of C major songs range from childhood tunes such as “Twinkle Twinkle Little Star” to timeless masterpieces such as John Lennon’s “Imagine.” Only John Lennon with his genius could turn C Major bittersweet, but there it is folks. I often think C major gets a bad rap from music snoots – Lennon made it work, it’s not just Twinkle Twinkle territory:

Varying the key will impact the feel, however the “positive” aspect of the emotions the music elicits remains firmly in the major. For example the track “It’s a Beautiful Day” by U2 is in D major (D Ionian).

4. Mode IV: Lydian mode

The second major mode, the fourth mode of the entire seven, is the Lydian mode, named after the ancient Kingdom of Lydia in Anatolia. It is the major scale with a raised fourth note (compared to the major scale), which as explained below gives it an entirely new sense of movement. The sequence of the steps is W, W, W, H, W, W, H and is the fifth of the original church modes though is not a commonly used one because of its character. Here, listen:

In “The Lydian Scale: Seeking the Ultimate Mysteries of Music”, Andrew Bishko does a fine job of uncovering the mysterious nature of the Lydian scale. He goes far in his explanation, but in sum, the entire reason for the dreamlike character of the Lydian scale is the augmented fourth degree (note). Compared to the major scale, it is raised by a half step. This small change violates what music theorist George Russell coined “tonal gravity,” the tendency for a feeling of openness to occur in the direction of the root to the fifth and a closing, and ending feeling, from the fifth to the root – a common musical resolution. Basically, an attempt to resolve the Lydian scale is difficult, as they augmented 4th creates a situation of little tension so there’s nothing to resolve. This creates a dreamy, floating feeling.

As Bishko writes, “Musically, it is quite literally going nowhere.” Interestingly, Bishko states that Russell has a term of musically going nowhere – horizontal.

5. Mode V: Mixolydian mode

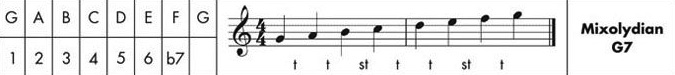

The final major scale here, the Mixolydian scale, is a major scale played with the fifth note as the root (or tonic). So, C major played from G is the G Mixolydian with the notes G, A, B, C, D, E, and F. While the Lydian differs from the Ionian (major) scale by only an augmented 4th, the Mixolydian differs with the Ionian only by a flat 7th. The sequence of the steps is W, W, H, W, W, H, W and often used in jazz improvisation, its special character derives from the major thirds and the minor sevenths. While its name was given by the Greeks as with all modes, and it was the seventh of the eight medieval church modes, the modern Mixolydian differs.

Mixolydian can be considered the “cool” one of the major modes, used extensively in jazz, the blues, and rock. The Mixolydian mode feels neither major nor minor and instead is known to give an exotic feel and to me – bittersweet. It has a seriousness, but also a sweetness to it, used by Bob Dylan in “Lay Lady Lay,” “Hey Jude” by the Beatles, and “All Apologies” by Nirvana. This mode can also rock. Songs such as “Sweet Child O’Mine” by Guns and Roses, “Sweet Home Alabama” by Lynyrd Skynyrd, and interestingly Lorde’s track “Royals” all employ the mixolydian mode. Phil Whitmer in “Here’s the Music Theory Behind Why Lorde’s Songwriting Is Objectively Kickass” on www.noisy.vice.com notes that “Sweet Home Alabama” and “Royals” ‘in fact not only use the same mode but in fact the same main chord progression D-C-G. Whitmer’s post is an excellent read that sheds light on the vibe and purpose of the Mixolydian mode: well-written, witty, informative.

Next up: the minor modes. And I must end by saying how odd it is that simply by switching the root of the exact same notes we can so drastically shift the emotions a set of those exact same notes bring.

Related: Music of the Minor Modes