Sound is a natural phenomenon, and music is this natural phenomenon harnessed and morphed by human minds and hands: an evolution of sound based on the principles of physics. Below we explore various expressions of this relationship between music/sound and the natural world.

The “Elegy for the Arctic”

In some instances, as in the following, humans use nature as inspiration for art in an attempt to honor the natural world and to inspire others to action. For example, on November 23, 2017, Italian composer and pianist Ludovico Einaudi premiered his composition “Elegy for the Arctic” floating on the Arctic Sea.

Inspired by a Greenpeace petition of 8 million people across the world demanding governments to cease oil drilling and destructive fishing, Einaudi wrote this piece and performed it floating in the Arctic Ocean, surrounded by the very icebergs that are at risk. The iceberg, a 2.6 x 10 meter, 2 ton, constructed iceberg, held Einaudi and his grand piano to perform this gorgeous piece, inspirational but haunting: his call to action in support of Arctic preservation and a chance to mourn a potential future of human error. The interaction between human music and the natural world here is figurative but very real.

Einaudi called the iceberg the “best stage in the world”

Great Stalacpipe Organ

The Great Stalacpipe Organ is an electrically actuated lithophone located in Luray Caverns, Virginia, USA. It is operated by a custom console that produces the tapping of ancient stalactites of varying sizes with solenoid-actuated rubber mallets in order to produce tones. The instrument’s name was derived from the resemblance of the selected thirty-seven naturally formed stalactites to the pipework of a traditional pipe organ along with its custom organ-style keyboard console. It was designed and implemented in 1956 over three years by  Leland W. Sprinkle inside the Luray Caverns near Shenandoah National Park in Virginia, USA.

Leland W. Sprinkle inside the Luray Caverns near Shenandoah National Park in Virginia, USA.

The Great Stalacpipe Organ appears at first to be a normal organ, but instead of using pipes, the organ is wired to soft rubber mallets poised to gently strike stalactites of varying lengths and thicknesses. When the keyboard is played, the entire subterranean landscape becomes a musical instrument. In order to achieve a precise musical scale, the chosen stalactites of the organ range over 3.5 acres, but due to the enclosed nature of the space, the full sound can be heard anywhere within the cavern. The organ was invented and built in 1954 by Leland Sprinkle, a mathematician and electronic scientist. It took him over three years to complete it.

Sprinkle created the Great Stalacpipe Organ over three years by finding and shaving appropriate stalactites to produce specific notes. He then wired a mallet for each stalactite that is activated by pressing an associated key on the instrument’s keyboard. The stalactites are distributed through approximately 3.5 acres (14,000 m2) of the caverns but can be heard anywhere within its 64-acre (260,000 m2) confines.

Amateur video with music in background excellent view of the size of the instrument

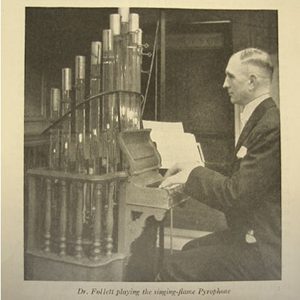

Pyrophone – fire breathing piano

Physicist and musician Georges Frédéric Eugène Kastner, 1852- 1882, was the son of French composer Jean-Georges Kastner, who took his father’s fondness of music and instruments to a new level with the invention of the pyrophone in 1870. This instrument is also known as a “fire-explosion organ” which emits notes that are caused by explosions, rapid combustion and  heating. In Kastner’s patent for his instrument, he explains that two parts hydrogen to one part oxygen in a glass tube, when united and combusted will create a chain of slight detonations. By using distances of thirds along the length of a glass tube from the bottom up, a number of explosions which match the vibrations needed to produce a sound in the tube will create a musical tone. By changing the height of the flame, the ratios between the explosions and the needed vibrations are disrupted and the sounds cease, allowing control of the instrument.

heating. In Kastner’s patent for his instrument, he explains that two parts hydrogen to one part oxygen in a glass tube, when united and combusted will create a chain of slight detonations. By using distances of thirds along the length of a glass tube from the bottom up, a number of explosions which match the vibrations needed to produce a sound in the tube will create a musical tone. By changing the height of the flame, the ratios between the explosions and the needed vibrations are disrupted and the sounds cease, allowing control of the instrument.

The Pyrophone made a splash in the last 1800s, as one Jean Henri Dunant wrote in 1875 in  Popular Science about these “singing flames” produced by the pyrophone which he deemed had a strong connection to the cosmos itself, having an ethereal quality. He poetically describes the process that Kastner describes in his patent which he calls “chemical harmonica.” Dunant explains to his audience of scientists that in order for sound to become pure, as in a musical note, “the impulse .. should be exactly similar in duration and intensity” to the intonations needed to create a note on the musical scale and thus becomes no longer “dull and confused,” but “clear and brilliant.” Dunant epically describes the sound produced by the pyrophone, writing that it resembles the sound of a human voice mixed with that of an Aeolian harp, “powerful, full of taste, and brilliant; with much roundness, accuracy, and fullness; like a human and impassioned whisper, as an echo of the inward vibrations of the soul.” (Popular Science Monthly, v7, 1875). With such a ringing endorsement, clearly, the pyrophone is an instrument to hear – not to mention the greatest part of all – it makes music with FIRE:

Popular Science about these “singing flames” produced by the pyrophone which he deemed had a strong connection to the cosmos itself, having an ethereal quality. He poetically describes the process that Kastner describes in his patent which he calls “chemical harmonica.” Dunant explains to his audience of scientists that in order for sound to become pure, as in a musical note, “the impulse .. should be exactly similar in duration and intensity” to the intonations needed to create a note on the musical scale and thus becomes no longer “dull and confused,” but “clear and brilliant.” Dunant epically describes the sound produced by the pyrophone, writing that it resembles the sound of a human voice mixed with that of an Aeolian harp, “powerful, full of taste, and brilliant; with much roundness, accuracy, and fullness; like a human and impassioned whisper, as an echo of the inward vibrations of the soul.” (Popular Science Monthly, v7, 1875). With such a ringing endorsement, clearly, the pyrophone is an instrument to hear – not to mention the greatest part of all – it makes music with FIRE:

https://en.m.wikisource.org/wiki/Popular_Science_Monthly/Volume_7/August_1875/The_Pyrophone

The Waterphone

Richard Waters was an American artist and inventor and sonic experimentalist who gained artistic traction from the 1960’s onward and is best know as the creator of The Waterphone. As opposed to the fire of the Pyrophone, The Waterphone uses water to warp and modify sound housed inside its resonators. The instrument is handmade of stainless steel and bronze and are known as “acoustic synthesizers. According to the Waterphone website, it is somewhere between the Tibetan Water Drum, the African Kalimba, and something called a Nail Violin. Waters crafted and honed his creative process for 40 years, using hot metal to create tonal rods tuned diatonically in “micro-tones.

Richard Waters was an American artist and inventor and sonic experimentalist who gained artistic traction from the 1960’s onward and is best know as the creator of The Waterphone. As opposed to the fire of the Pyrophone, The Waterphone uses water to warp and modify sound housed inside its resonators. The instrument is handmade of stainless steel and bronze and are known as “acoustic synthesizers. According to the Waterphone website, it is somewhere between the Tibetan Water Drum, the African Kalimba, and something called a Nail Violin. Waters crafted and honed his creative process for 40 years, using hot metal to create tonal rods tuned diatonically in “micro-tones.

The Waterphone is either suspended by a cord or held by its neck and can be played as a  stringed or percussion instrument with hands and fingers, mallets, or bows. It not only uses a natural element as part of its construction (water), but has been proven to interact with nature by successfully calling whales. The instrument has made a splash, so to speak, in cinema being included on film and TV soundtracks such as “Star Trek” the movie, “Poltergeist,” “Bugsy,” “Young Guns,” and more. In addition, it has been exhibited in galleries and museums such as the Smithsonian in DC, the Oakland Museum, the San Francisco Folk Art Museum to name a few. Documentaries have covered the instrument such as “Art Notes” (San Francisco’s public television, and the film short “Celestial Wave.” While Waters passed in 2013, his instruments continue. To be handcrafted and sold at the waterphone.com.

stringed or percussion instrument with hands and fingers, mallets, or bows. It not only uses a natural element as part of its construction (water), but has been proven to interact with nature by successfully calling whales. The instrument has made a splash, so to speak, in cinema being included on film and TV soundtracks such as “Star Trek” the movie, “Poltergeist,” “Bugsy,” “Young Guns,” and more. In addition, it has been exhibited in galleries and museums such as the Smithsonian in DC, the Oakland Museum, the San Francisco Folk Art Museum to name a few. Documentaries have covered the instrument such as “Art Notes” (San Francisco’s public television, and the film short “Celestial Wave.” While Waters passed in 2013, his instruments continue. To be handcrafted and sold at the waterphone.com.

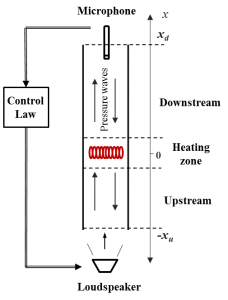

The Rijke Tube

This ultra-simple instrument creates one standing wave and therefore may qualify as more of a laboratory experience than rather than a playable performance tool. However, it falls in line with the other instruments in this post in that it directly harnesses and puts emphasis on natural elements at its core. Simply put, the Rijke tube turns heat into sound and creates a self-amplifying standing wave, an example of resonance.

It seems that inventors, scientists and musicians in the 19th century were intent on creating

sound with heat and fire, as physics professor P.L. Rijke of the Netherlands discovered the means to sustain sound with heat via an open ended tube in the same decade that Kessler patented his Pyrophone. Rijke used a glass tube 3.5 cm in diameter and 0.8 m in  length that housed a disc made of wire gauze. The disc was held through friction and heated until it glowed red. When the flame was removed, the tube emitted sound that diminished as the disc cooled and eventually died out.

length that housed a disc made of wire gauze. The disc was held through friction and heated until it glowed red. When the flame was removed, the tube emitted sound that diminished as the disc cooled and eventually died out.

Rijke moved on to use electrical heating which produced continuous heat and therefore continuous sound. further experiments at the time report that the sound from the Rijke tube was substantial, enough to shake the room and heard throughout the department. (John Wm. Strutt (Lord Rayleigh) (1879) “Acoustical observations,” Philosophical Magazine, 5th series, vol. 7, pages 149-162.)

The sound coming from the Rijke tube is created due to physics. It makes a “standing wave” that has a wavelength twice the length of the tube which creates a fundamental frequency. The standing wave is a wave caused by two wave motions occurring simultaneously, in this case the heat causing air movement due to convection is combined with the motion of the sound waves. The reason that the Rijke tube creates such loud sound is because the “pressure maximum” is constantly reinforced with the continual introduction of small bits of cool air during the process.

While that might be all a bit heady, it suffices to say that the human spirit of inventiveness continues in all forms, in this case we play with nature to create sound. It seems we will never stop tinkering and toying with these resources we find around us, a great reason to be alive.